“Effect of Enalapril on Survival in Patients with Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fractions and Congestive Heart Failure”

by the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) Investigators

N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 1;325(5):293-302. [free full text]

—

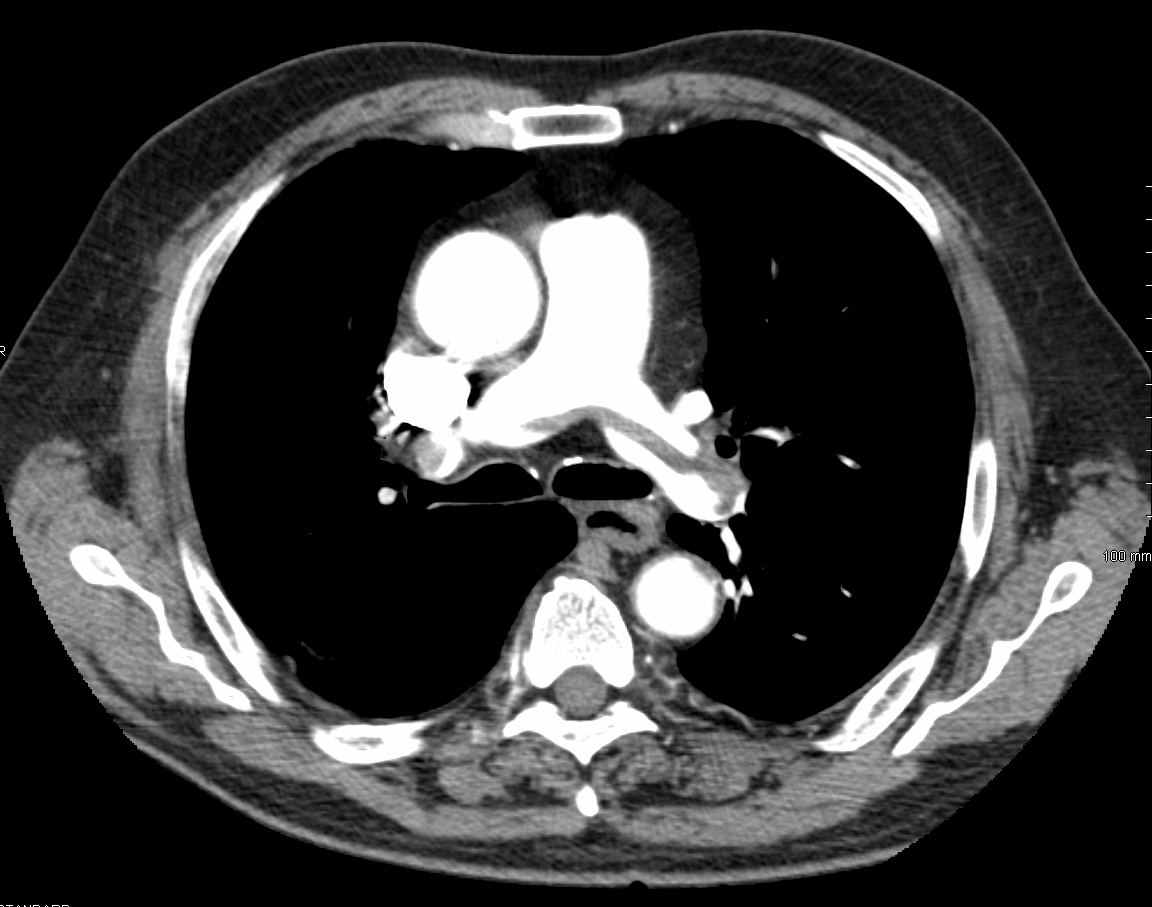

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) is a very common and highly morbid condition. We now know that blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) with an ACEi or ARB is a cornerstone of modern HFrEF treatment. The 1991 SOLVD trial played an integral part in demonstrating the benefit of and broadening the indication for RAAS blockade in HFrEF.

The trial enrolled patients with HFrEF and LVEF ≤ 35% who were already on treatment (but not on an ACEi) and had Cr ≤ 2.0 and randomized them to treatment with enalapril BID (starting at 2.5mg and uptitrated as tolerated to 20mg BID) or treatment with placebo BID (again, starting at 2.5mg and uptitrated as tolerated to 20mg BID). Of note, there was a single-blind run-in period with enalapril in all patients, followed by a single-blind placebo run-in period. Finally, the patient was randomized to his/her actual study drug in a double-blind fashion. The primary outcomes were all-cause mortality and death from or hospitalization for CHF. Secondary outcomes included hospitalization for CHF, all-cause hospitalization, cardiovascular mortality, and CHF-related mortality.

2569 patients were randomized. Follow-up duration ranged from 22 to 55 months. 510 (39.7%) placebo patients died during follow-up compared to 452 (35.2%) enalapril patients (relative risk reduction of 16% per log-rank test, 95% CI 5-26%, p = 0.0036). See Figure 1 for the relevant Kaplan-Meier curves. 736 (57.3%) placebo patients died or were hospitalized for CHF during follow-up compared to 613 (47.7%) enalapril patients (relative risk reduction 26%, 95% CI 18-34, p < 0.0001). Hospitalizations for heart failure, all-cause hospitalizations, cardiovascular deaths, and deaths due to heart failure were all significantly reduced in the enalapril group. 320 placebo patients discontinued the study drug versus only 182 patients in the enalapril group. Enalapril patients were significantly more likely to report dizziness, fainting, and cough. There was no difference in the prevalence of angioedema.

Treatment of HFrEF with enalapril significantly reduced mortality and hospitalizations for heart failure. The authors note that for every 1000 study patients treated with enalapril, approximately 50 premature deaths and 350 heart failure hospitalizations were averted. The mortality benefit of enalapril appears to be immediate and increases for approximately 24 months. Per the authors, “reductions in deaths and rates of hospitalization from worsening heart failure may be related to improvements in ejection fraction and exercise capacity, to a decrease in signs and symptoms of congestion, and also to the known mechanism of action of the agent – i.e., a decrease in preload and afterload when the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II is blocked.” Strengths of this study include its double-blind, randomized design, large sample size, and long follow-up. The fact that the run-in period allowed for the exclusion prior to randomization of patients who did not immediately tolerate enalapril is a major limitation of this study.

Prior to SOLVD, studies of ACEi in HFrEF had focused on patients with severe symptoms. The 1987 CONSENSUS trial was limited to patients with NYHA class IV symptoms. SOLVD broadened the indication of ACEi treatment to a wider group of symptoms and correlating EFs. Per the current 2013 ACCF/AHA guidelines for the management of heart failure, ACEi/ARB therapy is a Class I recommendation in all patients with HFrEF in order to reduce morbidity and mortality.

Further Reading/References:

1. Wiki Journal Club

2. 2 Minute Medicine

3. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure – Results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). 1987.

4. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: executive summary

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD