“Mortality and Morbidity in Patients Receiving Encainide, Flecainide, or Placebo”

The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST)

N Engl J Med. 1991 Mar 21;324(12):781-8. [full text]

—

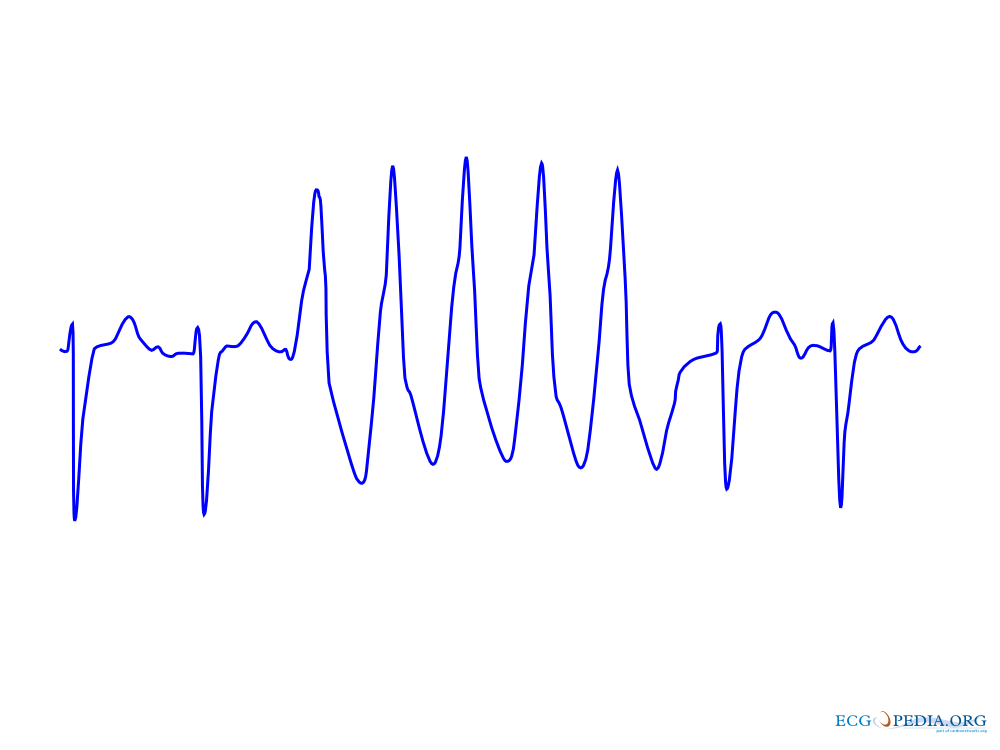

Ventricular arrhythmias are common following MI, and studies have demonstrated that PVCs and other arrhythmias such as non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) are independent risk factors for cardiac mortality following MI. As such, by the late 1980s, many patients with PVCs post-MI were treated with antiarrhythmic drugs in an attempt to reduce mortality. The 1991 CAST trial sought to prove what predecessor trials had failed to prove – that suppression of such rhythms post-MI would improve survival.

This trial took post-MI patients with PVCs (with no sustained VT) and reduced EF and randomized them to an open-label titration period in which encainide, flecainide, or moricizine was titrated to suppress at least 80% of the PVCs and 90% of the runs of NSVT. Patients were then either randomized to continuation of the antiarrhythmic drug assigned during the titration period or transitioned to a placebo. The primary outcome was death or cardiac arrest with resuscitation, “either of which was due to arrhythmia.”

The trial was terminated early due to increased mortality in the encainide and flecainide treatment groups. 1498 patients were randomized following successful titration during the open-label period, and they were reported in this paper. The results of the moricizine arm were reported later in a different paper (CAST-II). The RR of death or cardiac arrest due to arrhythmia was 2.64 (95% CI 1.60–4.36; number needed to harm = 28.2). See Figure 1 on page 783 for a striking Kaplan-Meier curve. The RR of death or cardiac arrest due to all causes was 2.38 (95% CI 1.59–3.57; NNH = 20.6). Regarding other secondary outcomes, cardiac death/arrest due to any cardiac cause was similarly elevated in the treatment group, and there were no significant differences in non-lethal endpoints among the treatment and placebo arms.

In this large RCT, the treatment of asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmias with encainide and flecainide in patients with LV dysfunction following MI resulted in increased mortality. This study provides a classic example of how a treatment that seems to make intuitive sense based on observational data can be easily and definitively disproven with a placebo-controlled trial with hard endpoints (e.g. death). Although PVCs and NSVT are associated with cardiac death post-MI and reducing these arrhythmias might seem like an intuitive strategy for reducing death, correlation does not equal causation. Modern expert opinion at UpToDate notes no role for suppression of asymptomatic PVCs or NSVT in the peri-infarct period. Indeed such suppression may increase mortality. As noted on Wiki Journal Club, modern ACC/AHA guidelines “do not comment on the use of antiarrhythmic medications in ACS care.”

Further Reading/References:

1. CAST @ Wiki Journal Club

2. CAST @ 2 Minute Medicine

3. CAST-I Trial @ ClinicalTrials.gov

4. CAST-II trial publication, NEJM 1992

5. UpToDate “Clinical features and treatment of ventricular arrhythmias during acute myocardial infarction”

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD