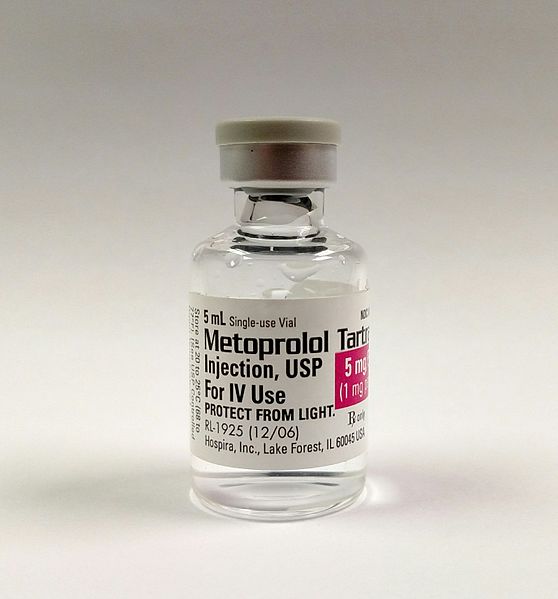

“Effects of extended-release metoprolol succinate in patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery: a randomised controlled trial”

Lancet. 2008 May 31;371(9627):1839-47. [free full text]

—

Non-cardiac surgery is commonly associated with major cardiovascular complications. It has been hypothesized that perioperative beta blockade would reduce such events by attenuating the effects of the intraoperative increases in catecholamine levels. Prior to the 2008 POISE trial, small- and moderate-sized trials had revealed inconsistent results, alternately demonstrating benefit and non-benefit with perioperative beta blockade. The POISE trial was a large RCT designed to assess the benefit of extended-release metoprolol succinate (vs. placebo) in reducing major cardiovascular events in patients of elevated cardiovascular risk.

The trial enrolled patients age 45+ undergoing non-cardiac surgery with estimated LOS 24+ hrs and elevated risk of cardiac disease, meaning: either 1) hx of CAD, 2) peripheral vascular disease, 3) hospitalization for CHF within past 3 years, 4) undergoing major vascular surgery, 5) or any three of the following seven risk criteria: undergoing intrathoracic or intraperitoneal surgery, hx CHF, hx TIA, hx DM, Cr > 2.0, age 70+, or undergoing urgent/emergent surgery.

Notable exclusion criteria: HR < 50, 2nd or 3rd degree heart block, asthma, already on beta blocker, prior intolerance of beta blocker, hx CABG within 5 years and no cardiac ischemia since

Intervention: metoprolol succinate (extended-release) 100mg PO starting 2-4 hrs before surgery, additional 100mg at 6-12 hrs postoperatively, followed by 200mg daily for 30 days. (Patients unable to take PO meds postoperatively were given metoprolol infusion.)

Comparison: placebo PO / IV at same frequency as metoprolol arm

Outcome:

Primary – composite of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, and non-fatal cardiac arrest at 30 days

Secondary (at 30 days)

-

-

-

- cardiovascular death

- non-fatal MI

- non-fatal cardiac arrest

- all-cause mortality

- non-cardiovascular death

- MI

- cardiac revascularization

- stroke

- non-fatal stroke

- CHF

- new, clinically significant atrial fibrillation

- clinically significant hypotension

- clinically significant bradycardia

-

-

Pre-specified subgroup analyses of primary outcome:

-

-

- by Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI)

- by sex, type of surgery, use of epidural or spinal anesthetic

-

Results:

9298 patients were randomized. However, fraudulent activity was detected at participating sites in Iran and Colombia, and thus 947 patients from these sites were excluded from the final analyses. Ultimately, 4174 were randomized to the metoprolol group, and 4177 were randomized to the placebo group. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics, pre-operative cardiac medications, surgery type, or anesthesia type between the two groups (see Table 1).

Regarding the primary outcome, metoprolol patients were less likely than placebo patients to experience the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, and non-fatal cardiac arrest (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.70-0.99, p = 0.0399). See Figure 2A for the relevant Kaplan-Meier curve. Note that the curves separate distinctly within the first several days.

Regarding selected secondary outcomes (see Table 3 for full list), metoprolol patients were more likely to die from any cause (HR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03-1.74, p = 0.0317). See Figure 2D for the Kaplan-Meier curve for all-cause mortality. Note that the curves start to separate around day 10. Cause of death was analyzed, and the only group difference in attributable cause was an increased number of deaths due to sepsis or infection in the metoprolol group (data not shown). Metoprolol patients were more likely to sustain a stroke (HR 2.17, 95% CI 1.26-3.74, p = 0.0053) or a non-fatal stroke (HR 1.94, 95% CI 1.01-3.69, p = 0.0450). Of all patients who sustained a non-fatal stroke, only 15-20% made a full recovery. Metoprolol patients were less likely to sustain new-onset atrial fibrillation (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.58-0.99, p = 0.0435) and less likely to sustain a non-fatal MI (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.57-0.86, p = 0.0008). There were no group differences in risk of cardiovascular death or non-fatal cardiac arrest. Metoprolol patients were more likely to sustain clinically significant hypotension (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.38-1.74, P < 0.0001) and clinically significant bradycardia (HR 2.74, 95% CI 2.19-3.43, p < 0.0001).

Subgroup analysis did not reveal any significant interaction with the primary outcome by RCRI, sex, type of surgery, or anesthesia type.

Implication/Discussion:

In patients with cardiovascular risk factors undergoing non-cardiac surgery, the perioperative initiation of beta blockade decreased the composite risk of cardiovascular death, non-fatal MI, and non-fatal cardiac arrest and increased the overall mortality risk and risk of stroke.

This study affirms its central hypothesis – that blunting the catecholamine surge of surgery is beneficial from a cardiac standpoint. (Most patients in this study had an RCRI of 1 or 2.) However, the attendant increase in all-cause mortality is dramatic. The increased mortality is thought to result from delayed recognition of sepsis due to masking of tachycardia. Beta blockade may also limit the physiologic hemodynamic response necessary to successfully fight a serious infection. In retrospective analyses mentioned in the discussion, the investigators state that they cannot fully explain the increased risk of stroke in the metoprolol group. However, hypotension attributable to beta blockade explains about half of the increased number of strokes.

Overall, the authors conclude that “patients are unlikely to accept the risks associated with perioperative extended-release metoprolol.”

A major limitation of this study is the fact that 10% of enrolled patients were discarded in analysis due to fraudulent activity at selected investigation sites. In terms of generalizability, it is important to remember that POISE excluded patients who were already on beta blockers.

Currently, per expert opinion at UpToDate, it is not recommended to initiate beta blockers preoperatively in order improve perioperative outcomes. POISE is an important piece of evidence underpinning the 2014 ACC/AHA Guideline on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation and Management of Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery, which includes the following recommendations regarding beta blockers:

-

-

- Beta blocker therapy should not be started on the day of surgery (Class III – Harm, Level B)

- Continue beta blockers in patients who are on beta blockers chronically (Class I, Level B)

- In patients with intermediate- or high-risk preoperative tests, it may be reasonable to begin beta blockers

- In patients with ≥ 3 RCRI risk factors, it may be reasonable to begin beta blockers before surgery

- Initiating beta blockers in the perioperative setting as an approach to reduce perioperative risk is of uncertain benefit in those with a long-term indication but no other RCRI risk factors

- It may be reasonable to begin perioperative beta blockers long enough in advance to assess safety and tolerability, preferably > 1 day before surgery

-

Further Reading/References:

1. Wiki Journal Club

2. 2 Minute Medicine

3. UpToDate, “Management of cardiac risk for noncardiac surgery”

4. 2014 ACC/AHA guideline on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and management of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines.

Image Credit: Mark Oniffrey, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD