“A Randomized Trial of Long-Term Oxygen for COPD with Moderate Desaturation”

by the Long-Term Oxygen Treatment Trial (LOTT) Research Group

N Engl J Med. 2016 Oct 27;375(17):1617-1627. [free full text]

—

The long-term treatment of severe resting hypoxemia (SpO2 < 89%) in COPD with supplemental oxygen has been a cornerstone of modern outpatient COPD management since its mortality benefit was demonstrated circa 1980. Subsequently, the utility of supplemental oxygen in COPD patients with moderate resting daytime hypoxemia (SpO2 89-93%) was investigated in trials in the 1990s; however, such trials were underpowered to assess mortality benefit. Ultimately, the LOTT trial was funded by the NIH and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) primarily to determine if there was a mortality benefit to supplemental oxygen in COPD patients with moderate hypoxemia as well to analyze as numerous other secondary outcomes, such as hospitalization rates and exercise performance.

The LOTT trial was originally planned to enroll 3500 patients. However, after 7 months the trial had randomized only 34 patients, and mortality had been lower than anticipated. Thus in late 2009 the trial was redesigned to include broader inclusion criteria (now patients with exercise-induced hypoxemia could qualify) and the primary endpoint was broadened from mortality to a composite of time to first hospitalization or death.

The revised LOTT trial enrolled COPD patients with moderate resting hypoxemia (SpO2 89-93%) or moderate exercise-induced desaturation during the 6-minute walk test (SpO2 ≥ 80% for ≥ 5 minutes and < 90% for ≥ 10 seconds). Patients were randomized to either supplemental oxygen (24-hour oxygen if resting SpO2 89-93%, otherwise oxygen only during sleep and exercise if the desaturation occurred only during exercise) or to usual care without supplemental oxygen. Supplemental oxygen flow rate was 2 liters per minute and could be uptitrated by protocol among patients with exercise-induced hypoxemia. The primary outcome was time to composite of first hospitalization or death. Secondary outcomes included hospitalization rates, lung function, performance on 6-minute walk test, and quality of life.

368 patients were randomized to the supplemental-oxygen group and 370 to the no-supplemental-oxygen group. Of the supplemental-oxygen group, 220 patients were prescribed 24-hour oxygen support, and 148 were prescribed oxygen for use during exercise and sleep only. Median duration of follow-up was 18.4 months. Regarding the primary outcome, there was no group difference in time to death or first hospitalization (p = 0.52 by log-rank test). See Figure 1A. Furthermore, there were no treatment-group differences in the primary outcome among patients of the following pre-specified subgroups: type of oxygen prescription, “desaturation profile,” race, sex, smoking status, SpO2 nadir during 6-minute walk, FEV1, BODE index, SF-36 physical-component score, BMI, or history of anemia. Patients with a COPD exacerbation in the 1-2 months prior to enrollment, age 71+ at enrollment, and those with lower Quality of Well-Being Scale score at enrollment all demonstrated benefit from supplemental O2, but none of these subgroup treatment effects were sustained when the analyses were adjusted for multiple comparisons. Regarding secondary outcomes, there were no treatment-group differences in rates of all-cause hospitalizations, COPD-related hospitalizations, or non-COPD-related hospitalizations, and there were no differences in change from baseline measures of quality of life, anxiety, depression, lung function, and distance achieved in 6-minute walk.

The LOTT trial presents compelling evidence that there is no significant benefit, mortality or otherwise, of oxygen supplementation in patients with COPD and either moderate hypoxemia at rest (SpO2 > 88%) or exercise-induced hypoxemia. Although this trial’s substantial redesign in its early course is noted, the trial still is our best evidence to date about the benefit (or lack thereof) of oxygen in this patient group. As acknowledged by the authors, the trial may have had significant selection bias in referral. (Many physicians did not refer specific patients for enrollment because “they were too ill or [were believed to have benefited] from oxygen.”) Another notable limitation of this study is that nocturnal oxygen saturation was not evaluated. The authors do note that “some patients with COPD and severe nocturnal desaturation might benefit from nocturnal oxygen supplementation.”

For further contemporary contextualization of the study, please see the excellent post at PulmCCM from 11/2016. Included in that post is a link to an overview and Q&A from the NIH regarding the LOTT study.

References / Additional Reading:

1. PulmCCM, “Long-term oxygen brought no benefits for moderate hypoxemia in COPD”

2. LOTT @ 2 Minute Medicine

3. LOTT @ ClinicalTrials.gov

4. McDonald, J.H. 2014. Handbook of Biological Statistics (3rd ed.). Sparky House Publishing, Baltimore, Maryland.

5. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “Certificate of Medical Necessity CMS-484– Oxygen”

6. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018 Dec;15(12):1369-1381. “Optimizing Home Oxygen Therapy. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report.”

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD

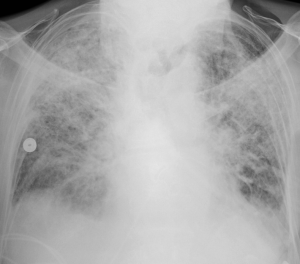

Image Credit: Patrick McAleer, CC BY-SA 2.0 UK, via Wikimedia Commons