“Effect of Early versus Deferred Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV on Survival”

N Engl J Med. 2009 Apr 30;360(18):1815-26. [free full text]

—

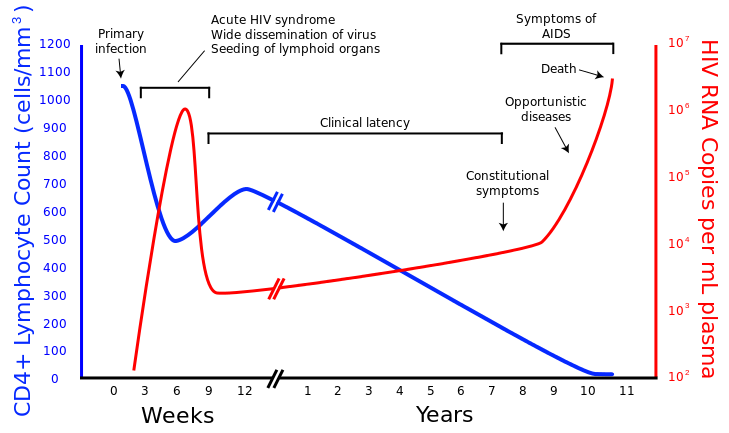

Until recently, the optimal timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) in asymptomatic patients with HIV had been a subject of investigation since the advent of antiretrovirals. Guidelines in 1996 recommended starting ART for all HIV-infected patients with CD4 count < 500, but over time provider concerns regarding resistance, medication nonadherence, and adverse effects of medications led to more restrictive prescribing. In the mid-2000s, guidelines recommended ART initiation in asymptomatic HIV patients with CD4 < 350. However, contemporary subgroup analysis of RCT data and other limited observational data suggested that deferring initiation of ART increased rates of progression to AIDS and mortality. Thus the NA-ACCORD authors sought to retrospectively analyze their large dataset to investigate the mortality effect of early vs. deferred ART initiation.

The study examined the cases of treatment-naïve patients with HIV and no hx of AIDS-defining illness evaluated during 1996-2005. Two subpopulations were analyzed retrospectively: CD4 count 351-500 and CD4 count 500+. No intervention was undertaken. The primary outcome was, within each CD4 sub-population, mortality in patients treated with ART within 6 months after the first CD4 count within the range of interest vs. mortality in patients for whom ART was deferred until the CD4 count fell below the range of interest.

8362 eligible patients had a CD4 count of 351-500, and of these, 2084 (25%) initiated ART within 6 months, whereas 6278 (75%) patients deferred therapy until CD4 < 351. 9155 eligible patients had a CD4 count of 500+, and of these, 2220 (24%) initiated ART within 6 months, whereas 6935 (76%) patients deferred therapy until CD4 < 500. In both CD4 subpopulations, patients in the early-ART group were older, more likely to be white, more likely to be male, less likely to have HCV, and less likely to have a history of injection drug use. Cause-of-death information was obtained in only 16% of all deceased patients. The majority of these deaths in both the early- and deferred-therapy groups were from non-AIDS-defining conditions.

In the subpopulation with CD4 351-500, there were 137 deaths in the early-therapy group vs. 238 deaths in the deferred-therapy group. Relative risk of death for deferred therapy was 1.69 (95% CI 1.26-2.26, p < 0.001) per Cox regression stratified by year. After adjustment for history of injection drug use, RR = 1.28 (95% CI 0.85-1.93, p = 0.23). In an unadjusted analysis, HCV infection was a risk factor for mortality (RR 1.85, p= 0.03). After exclusion of patients with HCV infection, RR for deferred therapy = 1.52 (95% CI 1.01-2.28, p = 0.04).

In the subpopulation with CD4 500+, there were 113 deaths in the early-therapy group vs. 198 in the deferred-therapy group. Relative risk of death for deferred therapy was 1.94 (95% CI 1.37-2.79, p < 0.001). After adjustment for history of injection drug use, RR = 1.73 (95% CI 1.08-2.78, p = 0.02). Again, HCV infection was a risk factor for mortality (RR = 2.03, p < 0.001). After exclusion of patients with HCV infection, RR for deferred therapy = 1.90 (95% CI 1.14-3.18, p = 0.01).

Thus, in a large retrospective study, the deferred initiation of antiretrovirals in asymptomatic HIV infection was associated with higher mortality.

This was the first retrospective study of early initiation of ART in HIV that was large enough to power mortality as an endpoint while controlling for covariates. However, it is limited significantly by its observational, non-randomized design that introduced substantial unmeasured confounders. A notable example is the absence of socioeconomic confounders (e.g. insurance status). Perhaps early-initiation patients were more well-off, and their economic advantage was what drove the mortality benefit rather than the early initiation of ART. This study also made no mention of the tolerability of ART or adverse reactions to it.

In the years that followed this trial, NIH and WHO consensus guidelines shifted the trend toward earlier treatment of HIV. In 2015, the INSIGHT START trial (the first large RCT of immediate vs. deferred ART) showed a definitive mortality benefit of immediate initiation of ART in patients with CD4 500+. Since that time, the standard of care has been to treat essentially all HIV-infected patients with ART (with some considerations for specific subpopulations, such as delaying initiation of therapy in patients with cryptococcal meningoencephalitis due to risk of IRIS). See further discussion at UpToDate.

Further Reading/References:

1. NA-ACCORD @ Wiki Journal Club

2. NA-ACCORD @ 2 Minute Medicine

3. INSIGHT START (2015), Pubmed, NEJM PDF

4. UpToDate, “When to initiate antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients”

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD

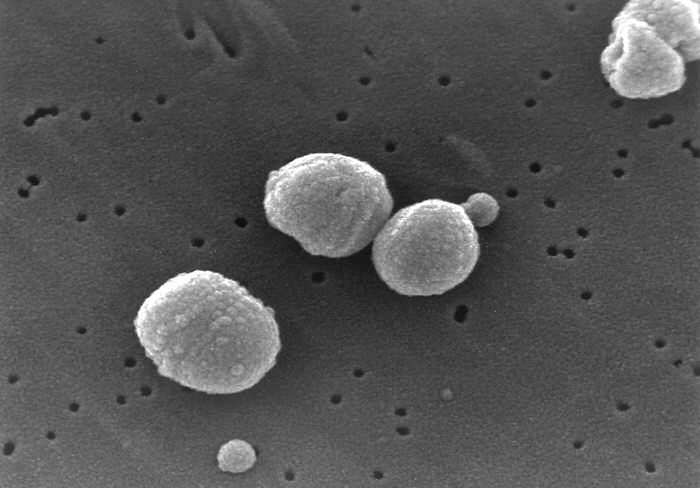

Image Credit: Sigve, CC0 1.0, via WikiMedia Commons