“Mortality Results from a Randomized Prostate-Cancer Screening Trial”

by the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial project team

N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1310-9. [free full text]

—

The use of prostate-specific-antigen (PSA) testing to screen for prostate cancer has been a contentious subject for decades. Prior to the 2009 PLCO trial, there were no high-quality prospective studies of the potential benefit of PSA testing.

The trial enrolled men ages 55-74 (excluded if hx prostate, lung, or colorectal cancer, current cancer treatment, or > 1 PSA test in the past 3 years). Patients were randomized to annual PSA testing for 6 years with annual digital rectal exam (DRE) for 4 years or to usual care. The primary outcome was the prostate-cancer-attributable death rate, and the secondary outcome was the incidence of prostate cancer.

38,343 patients were randomized to the screening group, and 38,350 were randomized to the usual-care group. Baseline characteristics were similar in both groups. Median follow-up duration was 11.5 years. Patients in the screening group were 85% compliant with PSA testing and 86% compliant with DRE. In the usual-care group, 40% of patients received a PSA test within the first year, and 52% received a PSA test by the sixth year. Cumulative DRE rates in the usual-care group were between 40-50%. By seven years, there was no significant difference in rates of death attributable to prostate cancer. There were 50 deaths in the screening group and only 44 in the usual-care group (rate ratio 1.13, 95% CI 0.75 – 1.70). At ten years, there were 92 and 82 deaths in the respective groups (rate ratio 1.11, 95% CI 0.83–1.50). By seven years, there was a higher rate of prostate cancer detection in the screening group. 2820 patients were diagnosed in the screening group, but only 2322 were diagnosed in the usual-care group (rate ratio 1.22, 95% CI 1.16–1.29). By ten years, there were 3452 and 2974 diagnoses in the respective groups (rate ratio 1.17, 95% CI 1.11–1.22). Treatment-related complications (e.g. infection, incontinence, impotence) were not reported in this study.

In summary, yearly PSA screening increased the prostate cancer diagnosis rate but did not impact prostate-cancer mortality when compared to the standard of care. However, there were relatively high rates of PSA testing in the usual-care group (40-50%). The authors cite this finding as a probable major contributor to the lack of mortality difference. Other factors that may have biased to a null result were prior PSA testing and advances in treatments for prostate cancer during the trial. Regarding the former, 44% of men in both groups had already had one or more PSA tests prior to study enrollment. Prior PSA testing likely contributed to selection bias.

PSA screening recommendations prior to this 2009 study:

-

-

- American Urological Association and American Cancer Society – recommended annual PSA and DRE, starting at age 50 if normal risk and earlier in high-risk men

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network: “a risk-based screening algorithm, including family history, race, and age”

- 2008 USPSTF Guidelines: insufficient evidence to determine balance between risks/benefits of PSA testing in men younger than 75; recommended against screening in age 75+ (Grade I Recommendation)

-

The authors of this study conclude that their results “support the validity of the recent [2008] recommendations of the USPSTF, especially against screening all men over the age of 75.”

However, the conclusions of the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC), which was published concurrently with PLCO in NEJM, differed. In ERSPC, PSA was screened every 4 years. The authors found an increased rate of detection of prostate cancer, but, more importantly, they found that screening decreased prostate cancer mortality (adjusted rate ratio 0.80, 95% CI 0.65–0.98, p = 0.04; NNT 1410 men receiving 1.7 screening visits over 9 years). Like PLCO, this study did not report treatment harms that may have been associated with overly zealous diagnosis.

The USPSTF reexamined its PSA guidelines in 2012. Given the lack of mortality benefit in PLCO, the pitiful mortality benefit in ERSPC, and the assumed harm from over-diagnosis and excessive intervention in patients who would ultimately not succumb to prostate cancer, the USPSTF concluded that PSA-based screening for prostate cancer should not be offered (Grade D Recommendation).

In the following years, the pendulum has swung back partially toward screening. In May 2018, the USPSTF released new recommendations that encourage men ages 55-69 to have an informed discussion with their physician about potential benefits and harms of PSA-based screening (Grade C Recommendation). The USPSTF continues to recommend against screening in patients over 70 years old (Grade D).

Screening for prostate cancer remains a complex and controversial topic. Guidelines from the American Cancer Society, American Urological Association, and USPSTF vary, but ultimately all recommend shared decision-making. UpToDate has a nice summary of talking points culled from several sources.

Further Reading/References:

#. PLCO @ 2 Minute Medicine

#. ERSPC @ Wiki Journal Club

#. UpToDate, Screening for Prostate Cancer

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD

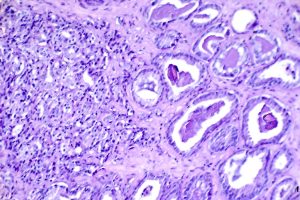

Image Credit: Otis Brawley, Public Domain, NIH National Cancer Institute Visuals Online