“Effects of Intensive Glucose Lowering in Type 2 Diabetes”

by the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Study Group

N Engl J Med. 2008 Jun 12;358(24):2545-59. [free full text]

—

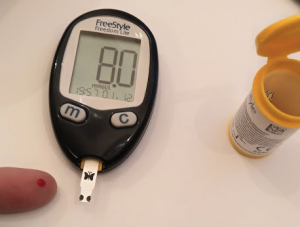

We all treat type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) on a daily basis, and we understand that untreated T2DM places patients at increased risk for adverse micro- and macrovascular outcomes. Prior to the 2008 ACCORD study, prospective epidemiological studies had noted a direct correlation between increased hemoglobin A1c values and increased risk of cardiovascular events. This correlation implied that treating T2DM to lower A1c levels would result in the reduction of cardiovascular risk. The ACCORD trial was the first large RCT to evaluate this specific hypothesis through comparison of events in two treatment groups – aggressive and less aggressive glucose management.

The trial enrolled patients with T2DM with A1c ≥ 7.5% and either age 40-79 with prior cardiovascular disease or age 55-79 with “anatomical evidence of significant atherosclerosis,” albuminuria, LVH, or ≥ 2 additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease (dyslipidemia, HTN, current smoker, or obesity). Notable exclusion criteria included “frequent or recent serious hypoglycemic events,” an unwillingness to inject insulin, BMI > 45, Cr > 1.5, or “other serious illness.” Patients were randomized to either intensive therapy targeting A1c to < 6.0% or to standard therapy targeting A1c 7.0-7.9%. The primary outcome was a composite first nonfatal MI or nonfatal stroke and death from cardiovascular causes. Reported secondary outcomes included all-cause mortality, severe hypoglycemia, heart failure, motor vehicle accidents in which the patient was the driver, fluid retention, and weight gain.

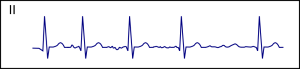

10,251 patients were randomized. The average age was 62, the average duration of T2DM was 10 years, and the average A1c was 8.1%. Both groups lowered their median A1c quickly, and median A1c values of the two groups separated rapidly within the first four months. (See Figure 1.) The intensive-therapy group had more exposure to antihyperglycemics of all classes. See Table 2.) Drugs were more frequently added, removed, or titrated in the intensive-therapy group (4.4 times per year versus 2.0 times per year in the standard-therapy group). At one year, the intensive-therapy group had a median A1c of 6.4% versus 7.5% in the standard-therapy group.

The primary outcome of MI/stroke/cardiovascular death occurred in 352 (6.9%) intensive-therapy patients versus 371 (7.2%) standard-therapy patients (HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.78-1.04, p = 0.16). The trial was stopped early at a mean follow-up of 3.5 years due to increased all-cause mortality in the intensive-therapy group. 257 (5.0%) of the intensive-therapy patients died, but only 203 (4.0%) of the standard-therapy patients died (HR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01-1.46, p = 0.04). For every 95 patients treated with intensive therapy for 3.5 years, one extra patient died. Death from cardiovascular causes was also increased in the intensive-therapy group (HR 1.35, 95% CI 1.04-1.76, p = 0.02). Regarding additional secondary outcomes, the intensive-therapy group had higher rates of hypoglycemia, weight gain, and fluid retention than the standard-therapy group. (See Table 3.) There were no group differences in rates of heart failure or motor vehicle accidents in which the patient was the driver.

Intensive glucose control of T2DM increased all-cause mortality and did not alter the risk of cardiovascular events. This harm was previously unrecognized. The authors performed sensitivities analyses, including non-prespecified analyses, such as group differences in use of drugs like rosiglitazone, and they were unable to find an explanation for this increased mortality.

The target A1c level in T2DM remains a nuanced, patient-specific goal. Aggressive management may lead to improved microvascular outcomes, but it must be weighed against the risk of hypoglycemia. As summarized by UpToDate, while long-term data from the UKPDS suggests there may be a macrovascular benefit to aggressive glucose management early in the course of T2DM, the data from ACCORD suggest strongly that, in patients with longstanding T2DM and additional risk factors for cardiovascular disease, such management increases mortality.

The 2019 American Diabetes Association guidelines suggest that “a reasonable A1c goal for many nonpregnant adults is < 7%.” More stringent goals (< 6.5%) may be appropriate if they can be achieved without significant hypoglycemia or polypharmacy, and less stringent goals (< 8%) may be appropriate for patients “with a severe history of hypoglycemia, limited life expectancy, advanced microvascular or macrovascular complications…”

Of note, ACCORD also simultaneously cross-enrolled its patients in studies of intensive blood pressure management and adjunctive lipid management with fenofibrate. See this 2010 NIH press release and the links below for more information.

-

-

- ACCORD Blood Pressure – NEJM, Wiki Journal Club

- ACCORD Lipids – NEJM, Wiki Journal Club

-

Further Reading/References:

1. ACCORD @ Wiki Journal Club

2. ACCORD @ 2 Minute Medicine

3. American Diabetes Association – “Glycemic Targets.” Diabetes Care (2019).

4. “Effect of intensive treatment of hyperglycaemia on microvascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: an analysis of the ACCORD randomised trial.” Lancet (2010).

Summary by Duncan F. Moore, MD

Image Credit: Omstaal, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons